Supreme Court Refuses to Wade in to Federal Circuit Claim Construction Precedent

By Sean Flaherty on April 7, 2021

Leave a comment

Author: Sean Flaherty

On Monday February 22, 2021, the Supreme Court denied certiorari to Akeva, L.L.C. in its dispute with Nike and Adidas regarding Akeva’s contention that the Federal Circuit applies separate and contradictory lines of authority to claim construction disputes. See No. 20-863, 2021 WL 666458 (U.S. Feb. 22, 2021)

In Akeva L.L.C. v. Nike, Inc., 817 F. App’x 1005, 1006 (Fed. Cir. 2020) a Federal Circuit panel of Justices Newman, O’Malley, and Chen ruled in a non-precedential opinion that the lower court “correctly construed ‘rear sole secured’ to exclude conventional fixed rear soles,” and thus affirmed the summary judgment decision of non-infringement issued by the District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina.

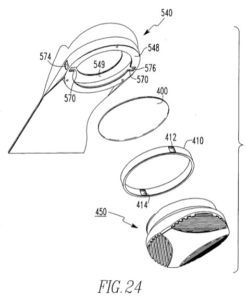

Pat No. 5,560,126 to Akeva, LLC provides that it “relates generally to an improved rear sole for footwear and, more particularly, to a rear sole for an athletic shoe with an extended and more versatile life…” Col. 1:9-12. Claim 25 reflected the exemplary dispute, which provided:

- A shoe comprising:

an upper having a heel region;

a rear sole secured below the heel region of the upper; and

a flexible plate having upper and lower surfaces and supported between at least a portion of the rear sole and at least a portion of the heel region of the upper, peripheral edges of the plate being restrained from movement relative to an interior portion of the plate in a direction substantially perpendicular to a major axis of the shoe so that the interior portion of the plate is deflectable relative to the peripheral edges in a direction substantially perpendicular to the major axis of the shoe.

Akeva argued that the ’126 patent covered shoes having either (i) a flexible plate with a conventional / non-removeable rear sole, or (ii) shoes having a removeable or rotatable [ie non-fixed] rear sole.

The District Court disagreed and found that the term “rear sole secured” was construed to mean “’rear sole selectively or permanently fastened, but not permanently fixed into position,’ which would not include conventional rear soles that do not either detach or rotate.”

There was no dispute that the accused shoes had fixed rear soles, so summary judgment was awarded to Nike and Adidas.

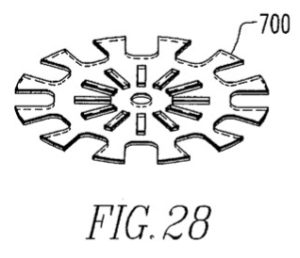

On appeal, Akeva reasserted that the ‘126 Patent includes shoes having both conventional and non-fixed rear soles. Akeva argued for example that Figure 28 of the ‘126 patent disclosed only the flexible midsole plate and not a removeable / rotatable rear sole:

Akeva also argued that the specification’s statement ““[t]he graphite insert also need not be used only in conjunction with a detachable rear sole, but can be used with permanently attached rear soles as well” demonstrated that the patent included shoes with conventional rear soles.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding instead that the ‘126 specification “clearly disclaims shoes with conventional fixed rear soles.” Akeva L.L.C. v. Nike, Inc., 817 F. App’x 1005, 1012 (Fed. Cir. 2020). It reasoned that “the invention is ‘[a] shoe [that] includes a heel support for receiving a rotatable and replaceable rear sole to provide longer wear.” To Akeva’s argument about Fig. 28, the Federal Circuit concluded that the specification indicated merely that “the shoe may also include a graphite insert.” It was held that the specification’s statement about use of the graphite insert with “permanently attached rear soles” was limited to those “permanently attached” rear soles that were nonetheless rotatable. The Federal Circuit further observed that the “’purpose of the invention’ is to overcome rear sole wear with a shoe having a detachable or rotatable rear sole that may additionally include a graphite insert.”

In its petition for certiorari, Akeva argued that the Supreme Court should decide whether the Federal Circuit’s line of cases finding a “heavy presumption” in favor of the plain meaning of claim terms, or else, the Federal Circuit’s line of cases taking a “holistic” approach toward claim terms, should govern claim construction.

Akeva argued that the “heavy presumption” line of cases permit divergence from a claim term’s plain and ordinary meaning “only” if it meets an “exacting” standard and demonstrates (i) a “clear” disclaimer of claim scope, or (ii) “clear” lexicography. Akeva argued in contrast that the Federal Circuit’s “holistic” approach permits courts to depart from the plain and ordinary meaning of the patent claims even if there is not “exacting “disclaimer, for example when the specification describes “the present invention,” “disparages” prior art, describes certain embodiments “repeatedly” and “consistently,” or provides an “implied” definition.

Akeva argued that the Federal Circuit failed to mention or address the plain meaning of “rear sole secured,” let alone the “heavy presumption” line of precedent. Akeva claimed that the plain meaning of “rear sole secured” denoted having a rear sole “fixed” to the shoe regardless of duration, and therefore encompassed Adidas and Nike’s accused athletic shoes.

Akeva cited Hill-Rom Servs., Inc. v. Stryker Corp., 755 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2014); Continental Circuits LLC v. Intel Corp., 915 F.3d 788 (Fed. Cir. 2019); and Absolute Software, Inc. v. Stealth Signal, Inc., 659 F.3d 1121, 1136-37 (Fed. Cir. 2011) in favor of the “heavy presumption” approach. For example, these authorities support contentions that a specification’s description of embodiments, use of the phrase “the present invention,” and disparagement of the prior art does not limit claim scope.

Akeva also recognized cases like Nystrom v. TREX Co., 424 F.3d 1136 (Fed. Cir. 2005), AquaTex Indus., Inc. v. Techniche Solutions, 419 F.3d 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2005), and Abbott Labs v. Sandoz, Inc., 566 F.3d 1282 (Fed. Cir. 2009) in applying the holistic approach. Akeva argued that “holistic cases are themselves often unpredictable as to what aspects of the specification or analysis thereof they might newly rely on to affect the scope of the claims-at-issue.”

According to Akeva, scholarly debate exists regarding the Federal Circuit’s “feuding” lines of authority on claim construction, citing Professors Bessen and Meurer in “Patent Failure: How Judges, Bureaucrats, and Lawyers Put Innovators at Risk.”

Ultimately, the Supreme Court’s denial of certiorari means that there will continue to be substantial dispute over claim construction with each side likely to cite valid yet seemingly incongruous law at one another. District Courts will cite that body of law which is more supportive of its decision, and even though appellate review of claim construction decisions is usually de novo, Federal Circuit panels will find latitude to affirm District Court decisions governing construction, regardless of the methodology applied.

About the author: Sean Flaherty is a partner in Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani’s Intellectual Property Practice Group. His practice focuses on litigation matters involving copyright, trademarks, trade secrets, and patents, as well as transactional matters related to intellectual property licensing. Mr. Flaherty is a registered patent attorney with a degree in Civil Engineering. Mr. Flaherty’s biography can be found here.