What the FBI’s “Project Titan” Criminal Complaint Reveals About Trade Secret Protection Efforts

By Louis Dorny on February 8, 2019

Leave a comment

Author: Louis Dorny

The FBI’s affidavit presented in support of a January 22, 2019 criminal complaint provides a rare glimpse into Apple’s effort to maintain trade secrets in its secretive Project Titan self-driving car operation. This glimpse was rare because any detailed effort to protect intellectual property in the form of a trade secret is often kept quiet to avoid providing any aid to a would-be thief.

The Background

Widely reported in recent days is the announcement of a second employee in six months to be accused by the FBI of stealing trade secrets from Apple’s self-driving car unit, known as “Project Titan.” Now, the feds have unsealed the January 22, 2019 criminal complaint against Jizhong Chen, a PhD-trained employee of Apple on the Project Titan team as a hardware developer. As alleged, Apple discovered the existence of over 2,000 photographs on Chen’s personally-owned computer, and subsequently learned Chen applied for two external jobs, including one at a China-based autonomous vehicle company — a purported direct competitor. Chen advised Apple he planned on leaving the country for China on January 22, 2019. The criminal complaint was filed the following day in the Northern District of California.

Apple was alerted to Chen after fellow employees spotted him taking photographs of the workspace where the project takes place. The FBI says Chen told Apple’s global security team that he backed up his work computer to a personal hard drive and computer as an insurance policy after being placed on a performance improvement plan by Apple. Apple’s security team found Chen had “over two thousand files containing confidential and proprietary Apple material, including manuals, schematics, and diagrams,” according to the charging document.

Not A Trade Secret Unless You Restrict Access

Similar to many jurisdictions that follow the Uniform Trade Secret Act (“UTSA”), California has specific requirements to protect against misappropriation of trade secrets. To qualify as a trade secret under section 3426.1 of California’s Civil Code, the owner of the trade secret must establish two elements: First, the trade secret must derive actual or potential independent economic value from not being generally known to the public or to other persons who can obtain economic value from the use or disclosure of the claimed secret. Second, the entity claiming trade secret must establish that it undertook “reasonable efforts under the circumstances” to maintain the secrecy of the trade secret.

So How Does Apple Restrict Access?

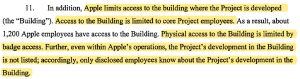

Excerpted below with highlighting supplied are paragraphs from the eight-page complaint, which can be found here.

Three software controls are evident to protect data. First, each user requires a password to access a database. Second, database access is restricted to a subset of project employees—likely on a need-to-know basis. Third, all access to information is logged and therefore capable of audit. An administrator must approve access. None of this is surprising. It has long been true that information stored on computer must require some reasonable form of restricted access. Morlife, Inc. v. Perry, 56 Cal.App.4th 1514, 1523 (1997). Trade-secret protection programs need not be as extensive as this to qualify under the statute. The standard is reasonable, which changes depending on the circumstances.

Physical access is restricted by limiting access to “core” employees with badge access while keeping the whereabouts secret. Such efforts are costly and likely warranted on “Project Titan,” but may be cost-prohibitive elsewhere. Again, efforts required to maintain secrecy are those that are “reasonable under the circumstances.” Moreover, “[t]he courts do not require that extreme and unduly expensive procedures be taken to protect trade secrets against flagrant industrial espionage. It follows that reasonable use of a trade secret including controlled disclosure to employees and licensees is consistent with the requirement of relative secrecy.” UTSA, Comment to § 1 (citation omitted); Senate Comment (1984) to California Civil Code § 3426.1.

While essential to put an employee or contractor on notice of the claim of a protected trade secrets with some specificity, a company would be unwise to rely on confidentiality agreements alone as a sufficient secrecy program. Courts have held that “[r]equiring employees to sign confidentiality agreements is a reasonable step to insure secrecy.” Whyte v. Schlage Lock Co. 101 Cal.App.4th 1443, 1454 (2002); MAI Systems Corp. v. Peak Computer, Inc., 991 F.2d 511, 521 (9th Cir. 1993) (applying California version of UTSA).

Training is often the weak link in an IP protection program due to cost or overreliance on employee agreements. Training is also a problem at the management level, which may not have a firm grip just what exactly compromises the trade secrets. On Project Titan we learn the most interesting tips of all: 1) training includes the importance of keeping details secret and avoiding intended and inadvertent leaks; 2) methods of ensuring protection of trade secrets, as well as device-specific policies; and 3) transmitting documents using secure mechanisms. In sum, an employee who has access to company trade secrets must know what is considered a trade secret. the contours of permissible use and the consequences of misuse—which can only be understood through an active effort to train. While no case in California has held that the failure to implement a training protocol for employees is unreasonable, that case may not be far off.

About the author: Lou Dorny is a partner in Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani’s Intellectual Property and Commercial Litigation Practice Groups. His practice focuses on intellectual property and high-technology matters, with a particular emphasis on trade secrets. Mr. Dorny’s biography can be found here.