An NFT Called “Copyright Infringement”

May 20, 2021 Leave a comment

21st Century Strategies for Patents, Trademarks and Copyrights

May 20, 2021 Leave a comment

Author: Hannah Brown

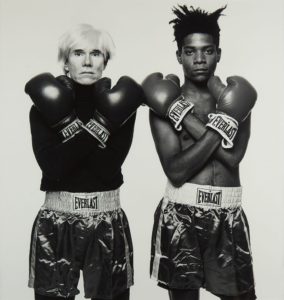

This story begins in 1982, when Andy Warhol met Jean-Michel Basquiat. Warhol and Basquait, two famous and successful artists, agreed to collaborate on an exhibition. In 1985, photographer Michael Halsband went to dinner with Basquait, which led to Halsband agreeing to photograph the poster for Basquait and Warhol’s collaborative to be titled “Paintings.”1 Halsband then took this famous picture of Warhol and Basquait on July 10, 1985:

This photo has been referred to as “perhaps one of the most iconic portraits of the two artists.”2

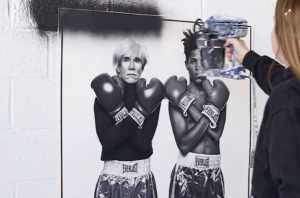

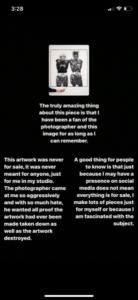

Fast forward to 2019, and enter New York artist CJ Hendry. Hendry is known for her realistic and incredibly detailed drawings. Hendry created an illustration based on Halsband’s photograph. Halsband sent Hendry a cease and desist letter, claiming copyright infringement.3 Halsband demanded that Hendry destroy her work. Complying, Hendry spray-painted over the piece. A screenshot of Hendry’s Instagram story shows the final result:

In fact, Hendry recorded herself spray-painting over the image with black paint:4

But, where things get really interesting is what Hendry did next. She turned the video into an NFT, or non-fungible token, and explained infra, and put it up for auction. The NFT was titled “Copyright Infringement.” As of April 16, 2021, the NFT was listed for sale at $6,685 at SuperRare.com.5 A search of SuperRare’s website shows Hendry’s NFT is no longer for sale on the site. How much the NFT sold for, if at all, is unknown.

Before diving into the issue of NFTs and Hendry’s video, the first issue is, did Hendry infringe Halsband’s work with her drawing of the photo? The answer is likely yes. Hendry creates incredible and realistic drawings. A quick look at her Instagram account shows her true talent and the realistic and detailed art that she can create with (what appears to be) colored pencils.

While an image of Hendry’s drawing of Halsband’s photograph is not available on her Instagram account, the below screenshot of her Instagram story gives us an idea of what it must have looked like:

It appears Hendry more or less reproduced the photograph in her drawing. A copyright of a work of art may be infringed by reproduction of the object itself. Home Art Inc. v. Glensder Textile Corp., 81 F.Supp. 551 (S.D.N.Y. 1948) (oil painting reproduced in scarf); Leigh v. Gerber, 86 F.Supp. 320 (S.D.N.Y. 1949) (painting reproduced by publication without consent in a magazine).

After receiving the cease and desist letter, Hendry took to Instagram to express her frustration with Halsband and his legal team, saying that she looks up to Halsband, and wondering how her drawing could not be seen as a compliment to him and his work. As noted above in her Instagram post, Hendry notes she was never going to sell the piece and was never going to profit off of it. However, a person can be liable for copyright infringement even if they have not gained profits from the infringing work. A plaintiff may recover statutory damages “whether or not there is adequate evidence of the actual damages suffered by plaintiff or of the profits reaped by defendant,” Harris v. Emus Records Corp., 734 F.2d 1329, 1335 (9th Cir. 1984), “‘to sanction and vindicate the statutory policy’ of discouraging infringement.” Peer Int’l Corp. v. Pausa Records, Inc., 909 F.2d 1332, 1336 (9th Cir. 1990) (quoting F.W. Woolworth Co. v. Contemporary Arts, Inc., 344 U.S. 228, 232 (1952)).6

Hendry could argue that her work was fair use of Halsband’s photograph under 17 U.S.C. § 107. In analyzing fair use, courts consider: (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. Id. But, as noted, Hendry did not take this issue to court and did not fight Halsband’s claim with a fair use defense. Instead, she destroyed the work and sold the video of her doing so as an NFT.

A brief explanation of an NFT is helpful. NFT stands for non-fungible token. NFTs are digital files, for example videos or digital art, and the buyer of the NFT gets to claim that they own the original digital work.7 NFTs are called “non-fungible” because they are unique, original, and cannot be interchangeable (unlike dollars bills or Bitcoin currency.) Your first thought may be: why would anyone ever pay for a digital work that they could download for free? You’re not alone in this thought, and as one author put it: “If all of this sounds bizarre, that’s because it is. The idea of paying for the symbolic ownership of a digital image that lives somewhere on the web and can be captured on a screenshot or right-click-download within seconds, is so alien it seems either idiotic or ironic.”8 But there is certainly a market for them, with videos and tweets selling for hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars.9

This leads to two other questions: (1) Does Hendry’s video of her painting over her drawing created using Halsband’s photograph, constitute copyright infringement? and (2) Can Hendry then copyright that video/NFT?

The answer to the first question is: maybe. While certainly Hendry’s video of her spray painting over her work is original content, it is likely that the video contains, at least in part, an image of Halsband’s copyrighted photograph (see the image above showing the drawing as Hendry begins to paint). However, it is also possible that her use of the photograph in the video as a whole was de minimis. “For an unauthorized use of a copyrighted work to be actionable, the use must be significant enough to constitute infringement.” Newton v. Diamond, 388 F.3d 1189, 1192–93 (9th Cir. 2004). “Even where there is some copying, that fact is not conclusive of infringement. Some copying is permitted. In addition to copying, it must be shown that this has been done to an unfair extent.” West Publ’g Co. v. Edward Thompson Co., 169 F. 833, 861 (E.D.N.Y.1909). If Hendry created a lengthy video of the spray painting, and the photograph was only in a small portion of that video, it is possible that this would not constitute infringement if her use of the photo was minimal when looking at the video as a whole.

The answer to the second question is: the NFT likely meets the criteria for copyrightability, but Halsband would probably object to the NFT becoming copyrighted. To be copyrightable, a work must be original and fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Hendry’s video of herself is original content (non-fungible literally means original and unique). But, the video would include Halsband’s copyrighted image. A copyright including another copyrighted image could lead to issues. Indeed, Hendry even titled her work “Copyright Infringement”!

In an analogous situation: a person cannot copyright a video of themselves if that video contains another’s copyrighted song. You may have heard of Nathan Apodaca, better known as 420Doggface208, or the man who went viral while skateboarding, drinking juice, and listening to Fleetwood Mac. Apodaca attempted to mint the video of himself as an NFT. But, because the video contained copyrighted material, i.e. the song, Stevie Nicks allegedly would not agree to Apodaca creating an NFT featuring her song.10

In fact, Halsband probably could have objected to Hendry making the video into an NFT, and profiting off of it, in the first place, due to use of his photograph. Halsband had sent Hendry a cease and desist letter already, and nothing would have stopped him from doing so again, this time requesting she desist from selling the NFT in an auction. Certainly, the point of Hendry’s NFT was to destroy what Halsband deemed an infringing work, and the NFT contained an image of that work. But, as noted above, Halsband may lose due to the de minimis defense.

With NFTs becoming more and more popular and profitable, this leads to an important piece of advice for anyone looking to create an NFT: consider whether your NFT is using another’s intellectual property. This could be use of a copyrighted image or even a song within the NFT. There does not appear to be any intellectual property requirements for creating an NFT; the creator does not have to certify that their work is completely their own creation.11 There is no agency needed to “approve” or “register” the NFT like is done when one seeks to register a copyright or trademark. It is important for creators of NFTs to review their work to ensure it is their original content, or that they have the permission from the author of the work, and that nothing they are putting online will get them in trouble.

About the author: Hannah Brown is an associate and member of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani’s Intellectual Property Practice Group, specializing in trademark, copyright, and patent litigation. She is a former law clerk to the Hon. Janis Sammartino and Hon. Cynthia Bashant of the U.S. District Court, Southern District of California.

________________________________________________________________________

1 https://www.swanngalleries.com/news/photographs-and-photobooks/2020/06/the-making-of-a-portrait-michael-halsbands-photograph-of-andy-warhol-and-jean-michel-basquiat/

2 https://www.swanngalleries.com/news/photographs-and-photobooks/2020/06/the-making-of-a-portrait-michael-halsbands-photograph-of-andy-warhol-and-jean-michel-basquiat/

3 https://hypebeast.com/2021/4/cj-hendry-copyright-infringement-nft-auction-superrare-release

4 https://hypebeast.com/2021/4/cj-hendry-copyright-infringement-nft-auction-superrare-release

5 https://hypebeast.com/2021/4/cj-hendry-copyright-infringement-nft-auction-superrare-release

6 This would be different if Hendry were fighting a criminal copyright infringement claim. To prevail on an allegation of criminal copyright infringement, a plaintiff must establish “infringement, that the infringement was willful, and that it was engaged in for profit.” Mattel, Inc. v. MGA Ent., Inc., 782 F. Supp. 2d 911, 1042 (C.D. Cal. 2011) (quoting United States v. Bily, 4066 F. Supp. 7266, 733 (E.D. Pa. 1975)).

7https://www.theverge.com/22310188/nft-explainer-what-is-blockchain-crypto-art-faq

8 https://www.wired.com/story/nfts-boom-collectors-shell-out-crypto/

9 .

10 https://www.lamag.com/article/nft-law-copyright/

11 https://help.foundation.app/en/articles/4742869-a-complete-guide-to-minting-an-nft#:~:text=Mint%20your%20NFT%3A%20Confirm%20that,the%20same%20with%20your%20wallet.